Maryland Falling Behind in CAFO Pollution Control

The Chesapeake Bay is in deep trouble from over-pollution. Years of half-hearted interstate efforts to check polluting emissions and restore the health and vitality of the nation's largest estuary have failed. The Environmental Protection Agency’s Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) plan for the Bay represents the Chesapeake's last, best chance of recovery.

To meet the TMDL, states must relentlessly force all polluters to sharply reduce their discharges. But a new issue alert from the Center for Progressive Reform reveals that Maryland—the state generally thought to be a regional leader in anti-pollution efforts—is lagging far behind in its implementation of the TMDL.

The economic sector most resistant to these changes is agriculture. Approximately half the pollution flowing into Chesapeake Bay comes from agriculture, but the industry has largely escaped regulation. The powerful farm lobby is desperate to hold on to this privileged position. One of its most heated battles has been against states’ efforts to curtail pollution from large animal feeding operations, most of which raise chickens.

Maryland is home to at least 588 large animal farms, known as concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) and Maryland animal feeding operations (MAFOs). To meet the TMDL, the state has committed to eliminating the discharge of 248,000 pounds-per-year of nitrogen and 41,000 pounds-per-year of phosphorus from all animal feeding operations in the state by 2025. Meeting this goal will require robust state oversight.

Falling Behind

Three years into the process, however, and Maryland has fallen far behind in permitting these facilities, missing a crucial opportunity to reduce pollution to meet the TMDL. Issuing permits is the only way to compel these facilities to follow certain best practices to limit pollutants flowing into the Bay. The Maryland Department of the Environment (MDE) has not registered 26 percent of Maryland’s CAFOs and MAFOs. In particular:

- The permit writers are behind: 87 out of a total of 506 complete applications have yet to be processed, leaving operators with no clear requirements to reduce pollution and MDE with no enforceable conditions.

- The CAFO program is understaffed, relying on three permit writers and the same number of inspectors. A loss of even one employee can cut the program’s productivity in half, as occurred in 2012.

- Many of the applications MDE receives are incomplete: 65 of 540 CAFOs lack the required comprehensive nutrient management plans (CNMPs) that dictate how the facility is to operate to protect water quality.

- MDE has so far given the industry a free ride: it has yet to collect application and annual fees for CAFO permits, which are $120 for small CAFOs, $600 for medium CAFOs, and $1,200 for large CAFOs. There are no fees for MAFO coverage. Collecting these fees would ensure that the program has sufficient resources to hire additional permit writers and inspectors.

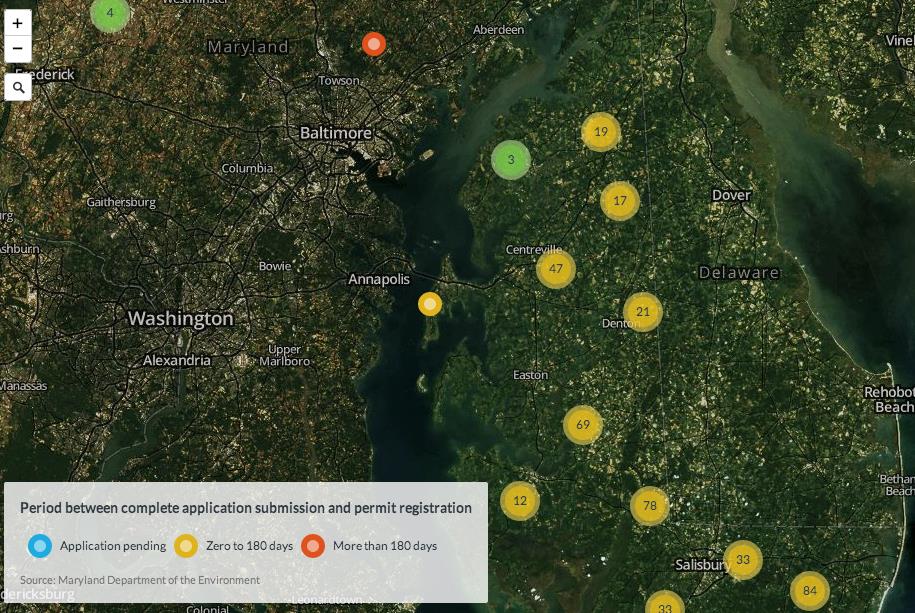

Mapping Maryland’s Animal Feeding Operations

An interactive feature prepared for CPR by the Chesapeake Commons maps the location of the CAFOs and MAFOs in Maryland. The map illustrates the time it takes MDE to process permits and the time it takes for a farm to submit a complete application. The map is available at http://www.progressivereform.org/mdcafomap.cfm.

Recommendations

- MDE should immediately begin to assess annual permit fees for CAFOs, both those that have permits and those with pending permits.Maryland's program is understaffed, unable to keep up with permit applications and inspections. As a first and long-overdue step, MDE must begin assessing permit fees. These fees ensure that a facility that pollutes the environment shoulders the full cost of regulating its operations—including processing and inspections—rather than foisting the cost onto the public. MDE has waived application and annual permit fees since the program began in 2010. The agency should immediately end this grace period and ensure that the permit and annual fees are assessed and reflect the anticipated cost of administering the permit.

- MDE should first process permits for operations with the most capacity to pollute, including the largest facilities and those that are located near an impaired waterway. While assessing user fees will help fund the program and allow it to hire more permit writers, the agency will still face a backlog. The agency should prioritize which permits it processes first. It should target the facilities with the most potential to pollute the Chesapeake Bay, including the largest facilities and those near impaired waters.

- MDE must identify additional avenues for technical assistance with comprehensive nutrient management plans. The CAFO program uses a one-size-fits-all general permit no matter the type or size of the operation or its proximity to an impaired water body. To supplement this basic general permit, CAFOs and MAFOs are required to develop and submit management plans that cover every aspect of the operation. These plans are critical to responsible management of waste. For CAFOs, the plans are developed by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) or by NRCS-certified technical service providers (TSPs). Over the course of the program, the technical assistance available has not kept up with the demand for these plans. The state must immediately identify additional avenues for technical assistance, including requiring MDE, MDA, and NRCS to develop a plan to expedite certification of additional TSPs.

- MDE should increase the number of physical, on-site inspections of MAFOs. The rate of inspections for MAFOs is significantly lower than the inspection rate for CAFOs. MDE should increase the number and frequency of physical, on-site inspections of these operations to ensure that they do not in fact discharge and are properly permitted. In FY 2012, MDE did not inspect a single MAFO. In 2013, it set an ambitious inspection target rate of more than 50 percent. Yet by July the agency had only inspected 15 percent of MAFOs.

- EPA should increase spot inspections of Chesapeake Bay CAFOs and accelerate the promulgation of a new rule to tighten controls on these sources. EPA and the Chesapeake Bay Foundation (CBF) entered into a weak agreement this past summer that postponed a broad nationwide CAFO rule until at least 2018, just seven short years before the Bay TMDL pollution-reduction deadline will arrive. Instead, EPA agreed to evaluate the state CAFO programs and inspect a limited number of CAFOs in the watershed. EPA should vigorously assess state programs, including increased spot checks of CAFOs in the region. It must also accelerate the timeline for a new rule, which will bring more CAFOs under federal regulation and begin to account for agriculture’s true impact on watersheds across the nation.

Allowing CAFOs to slip off the regulatory agenda would prevent the reduction of hundreds of thousands of pounds of pollution in Maryland alone. No amount of pollution reduction can be left on the table if the watershed is to meet the TMDL.

- Read the Issue Alert: Falling Behind: Processing and Enforcing Permits for Animal Agriculture in Maryland is Lagging, CPR Issue Alert #1310, by CPR President Rena Steinzor and CPR Policy Analyst Anne Havemann, November 2013. Also see the day-of release blog post, and the news release.

- Read the follow-up letter to MDE from Steinzor and Havemann urging the Department to stop waiving pollution permit application fees for CAFOs and MAFOs.

- Read the Baltimore Sun op-ed. "Why are polluters getting discounts?" by Rena Steinzor, in the December 27, 2013 Baltimore Sun.

- Read the related editorial memorandum: Money Left on the Table: Why Is the Maryland Department of the Environment Letting Taxpayers Subsidize Chesapeake Bay Polluters?, December 17, 2013, by Rena Steinzor and Anne Havemann.

- Webinar. Watch and listen to the authors' November 26, 2013, webinar on the report.

CPR is grateful to the Town Creek Foundation and the Rauch Foundation for their support of this project.