Last fall, in a speech I gave at an environmental justice event in Los Angeles, I ruffled some feathers with an impromptu line that went something like this: “Believe it or not, federal environmental statutes say nothing directly about environmental justice.” During the “Q & A” I was challenged by an environmental activist and lawyer who listed various ways that advocates had successfully used federal environmental statutes to address inequalities in many of California’s minority and low-income communities.

I saw immediately that I had not been clear. For what I meant was that although environmental statutes could be used to further the interests of social justice, the terrain was not landscaped for that purpose. It took activists with imagination and grit to climb the peaks my questioner was talking about. It took lawyers who could scan the glaciers of the federal code and find a foothold—a place where you could jam your steel-toothed boot, stabilize your momentum, and launch yourself forward. (EPA policy analyst Abby Hall and I expand on our theory of regulatory “footholds”—and also regulatory “rope lines”—here.)

Like community lawyers, policy makers need footholds too. EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson has made environmental justice a pillar of her tenure. But many of our environmental statutes, because they pre-date the modern environmental justice movement, were not developed with this priority in mind. So Administrator Jackson asked her lawyers to survey the landscape of environmental authorities for legal standards and directives that would provide the positioning and leverage to promote “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income.” EPA’s lawyers then catalogued those footholds and put them in a guide intended for use across the agency.

Like community lawyers, policy makers need footholds too. EPA Administrator Lisa Jackson has made environmental justice a pillar of her tenure. But many of our environmental statutes, because they pre-date the modern environmental justice movement, were not developed with this priority in mind. So Administrator Jackson asked her lawyers to survey the landscape of environmental authorities for legal standards and directives that would provide the positioning and leverage to promote “the fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income.” EPA’s lawyers then catalogued those footholds and put them in a guide intended for use across the agency.

In an admirable display of integrity and transparency, EPA has now publicly released that guide for all lawyers, activists, and citizens to see – and perhaps use.

Full text

|

|

|

|

Today’s question: When are flood waters not “flood waters”? We New Orleanians have become fluent in all things subaqueous; last week three Texans sitting on the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals took their turn.

Yes, we’re talking about Katrina. Or, more specifically, its flood waters, which busted federal levees in fifty places, swamped 80% of New Orleans, and caused 800 deaths in the urban area. It is beyond argument that federal malfeasance played a key role. But sovereign immunity under the 1928 Flood Control Act (FCA) seemed sure to prevent residents from pursuing any flood-based claims against their government.

Yet as recent developments suggest, the case for immunity may not be nearly so open and shut.

Back in the 1920s, when the federal government assumed responsibility for levees on the Lower Mississippi, Congress worried that such a mammoth endeavor could expose the country to overwhelming liability. So they wrote into the FCA an immunity provision: “[no] liability of any kind shall attach to . . . the United States for any damage from or by floods or flood waters at any place.” This sweeping language has proved remarkably steadfast, if not occasionally abhorrent. Take, for instance, the time when federal operators idiotically opened floodgates of a recreational reservoir without first warning a group of waterskiers, one of whom was summarily sucked down the vortex and killed. In James v. United States(1986)a majority of the Supreme Court found government immunity too clear to avoid, leaving a trio of dissenting justices wailing about an outcome they called both “perverse” and “barbaric.”

Full textLet’s stipulate: EPA’s withdrawal of a stronger ozone rule was the low point. And for many, a betrayal, a sedition, the nation’s biggest sell-out since Dylan went electric (or played China, take your pick).

Still, Jackson’s EPA has accomplished a great deal. Last week the EPA showcased new policy devoted to one issue with which Jackson has associated herself since day one: environmental justice.

The policy is called Plan EJ 2014, the agency’s comprehensive environmental justice strategy, planned to correspond with the 20th anniversary of President Clinton’s formative executive order on environmental justice (full disclosure: I was involved in the development of some parts of Plan EJ 2014 when I was in the Obama administration). The planoffers a road map for integrating environmental justice and civil rights into EPA’s daily work, including rulemaking, permitting, compliance and enforcement, community-based programs and coordination with other federal agencies. Jackson’s EPA deserves credit for making EJ an A-list priority, establishing a political-level, highly visible EJ advisor, and establishing this plan. Plans, of course, are only as good as their implementation, but this is a significant first step.

Full text Imagine you are building a beach house somewhere on the Gulf Coast and that I had some information about future high tides that would help you build a smarter structure, avoid flood damage, and save money in the long-run. Would you want that information?

Imagine you are building a beach house somewhere on the Gulf Coast and that I had some information about future high tides that would help you build a smarter structure, avoid flood damage, and save money in the long-run. Would you want that information?

Not if you follow the reasoning of Representatives Steve Scalise of Louisiana or John Carter of Texas. Both are concerned about the Obama administration’s recent efforts to make federal programs stronger and more resilient in the face of climate change. Scalise sponsored an amendment (H.AMDT. 467 to H.R. 2112) that prevents the Department of Agriculture (USDA) from pursuing its plan to assess climate vulnerabilities in its programs. Carter did the same (H.AMDT. 378 to H.R. 2017) for the Department of Homeland Security (DHS). And this month the Republican-led House of Representatives, with little fanfare, passed both initiatives (Scalise roll call, Carter roll call). I doubt either proposal will move past the Senate, but these efforts show how far some in the Republican Party have drifted from the geographic realities of their own states. And they underline the point that in the next election cycle Republicans seem likely to oppose any initiative whatsoever intended to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions or help with adapting to a changed world.

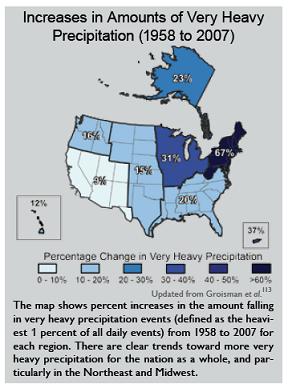

Forgive me for saying so, but our climate is changing. In the last 50 years, the ambient temperature in the United States has risen 2 degrees Fahrenheit. Overall precipitation in that time has increased by 5 percent. The amount of rain falling in the heaviest downpours in the United States has increased an average of 20 percent in the past century. In the last 40 to 50 years, many types of extreme weather events like heat waves and droughts have become more frequent and intense. Coastal storms in the Pacific and Atlantic have also intensified. And in the last half-century, sea level has risen up to 8 inches or more along some areas of the coastal United States. These trends are expected to continue or accelerate into the future. This information and more is available in the 2009 report, "Global Climate Change Impacts in the United States," issued by the U.S. Global Change Research Program (USGCRP), a consortium of thirteen federal agencies and departments. This peer-reviewed survey synthesizes a mountain of direct observations and other data accumulated over the last one hundred years.

Full textCopenhagen—Denmark’s famed "Little Harbor Lady," or in English, "Little Mermaid," has had her share of antics and perils. She’s been photographed by millions in Copenhagen’s harbor, carted off and shown at the 2010 World Fair in Shanghai, beheaded (several times), dynamited, splashed with pink paint, and enveloped in a Burqua. An environmental nerd for all occasions, I look at her longing face and wonder, How long before the rising sea swallows her up? Bolted to that rock in the sea, a shaft a concrete now inserted into her neck, what will she do? Or, for that, matter, the thousands of others who call coastal Copenhagen home. Is anyone thinking about this?

Many experts expect the world’s seas to rise somewhere between 1 to 1.5 meters this century, depending on location (and, of course, it could be more). Add to this a potential for stronger storms and much higher storm surges and you see why cities like Copenhagen, London, New York, and Miami are all in the crosshairs.

Danish experts have begun using computer-enhanced mapping techniques to predict what a high-tide of 2.26 meters—what they believe a "20-year event" might look like in 2110—would do to the city. The result leaves an inner city map covered in blue, including the Danish Stock Exchange, the Royal Library, and the city’s stunning Opera House. For this reason, the country is developing a proposal for a dike along Copenhagen’s North Harbor and an area called Kalveboderne to protect some of the city’s most treasured assets. For areas lying outside the protected region, which includes the Opera House, engineers are considering elevating roads and introducing architectural adjustments.

Back in New Orleans, where I live, we are also strengthening our fortress walls. At the opening of hurricane season this month, city residents took comfort (perhaps) in the strongest flood-control system ever constructed for the region. My favorite part is the Lake Borgne Barrier, a 1.8-mile-long castle-toothed wall, anchored by 66-inch-wide, 144-foot-deep concrete columns. The structure, which cost $1.1 billion and was built in just two years, is designed to block the kind of crashing hurricane surge brought by Hurricane Katrina, which in 2005 swept through the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway and Industrial Canal into the heart of New Orleans.

As I continually remind my students, resistance, while expensive and complicated, is not always futile....

Full textBonn--At a climate conference in Germany, with lager in hand, I was prepared to ponder nearly any environmental insult or failure. But rat pee? Really?

The urine of rats, as it turns out, is known to transmit the leptospirosis bacteria which can lead to high fever, bad headaches, vomiting, and diarrhea. During summer rainstorms in São Paulo, Brazil, floodwaters send torrents of sewage, garbage, and animal waste through miles of hillside slums and shanties. Outbreaks of leptospirosis often follow the floods. And in a metropolitan region of 20 million people, that’s a public health emergency.

I learned this and more at the 2nd World Congress on Cities and Adaptation to Climate Change, organized by ICLEI-Local Governments for Sustainability and the World Mayors Council on Climate Change, with support from the U.N. Human Settlements Programme. The event brought together 600 delegates, including mayors and UN officials, to address what may be this century’s defining challenge: keeping up with the climate.

While some of our national politicians continue to ignore basic climate science, and while I continue to rail against my local climate-denying weatherman who just last month spoke to my kids’ elementary school, the rest of the world is getting on with life. Specifically, scores of municipal governments from all over the world—rich and poor, iconic and ordinary—are beginning to make plans for adjusting to a planet that is going to be warmer, wetter, and just plain weirder.

In consultation with the World Bank, the City of Jakarta, Indonesia, has launched an assessment of geographical hazards, socioeconomic vulnerabilities, and institutional weaknesses now posed by rising seas, hotter temperatures, and swifter storms. This coastal megacity, 40 percent of which lies below sea level and is sinking because of groundwater depletion, is developing comprehensive disaster management programs, plans for coastal fortification, and new storm water systems. Half-a-world away, the city of Toronto has employed sophisticated computer modeling and a set of 1,700 plausible future scenarios to prepare for the impacts of stronger snowstorms and wilder floods. They have excel spreadsheets (and accompanying PowerPoint slides) on just about everything—traffic-light outages, sewer overflows, falling bridges, you name it. And down south in São Paulo, city officials are calling for vital “slum upgrades,” safer zoning, and, yes, improvements to sanitation and public-health networks to prevent and treat leptospirosis.

Full textIf you’ve ever visited the Great Smoky Mountains National Park—one of the most visited national parks in the United States—you have Horace Kephart and George Masa to thank. These two men, the first a travel writer, the second a landscape photographer from Osaka, Japan, each settled among those six-thousand foot peaks with intentions of starting a new life in the American wild. Unfortunately, the timber industry had gotten there first and was soon mowing down forests at the rate of 60 acres per day. Distressed by such calamity, Kephart and Masa organized a diverse grassroots campaign to raise millions of dollars to save the area. Fueled by church donations, high school fundraisers, and other activities, the campaign eventually enabled the federal government, through a public-private partnership, to set aside land for what would finally become by 1940, a protected, 814-square-mile expanse of America’s Great Outdoors.

On Wednesday, President Barack Obama invoked the memory of Kephart and Masa before a cheerful audience in the East Room of the White House, as he reported on his administration’s centerpiece conservation strategy known as the America’s Great Outdoors Initiative. I was there, squeezed between two-big shouldered men and surrounded by dozens of outdoor enthusiasts: ranchers, farmers, hunters, anglers, corporate executives, tribal representatives, backpackers, environmental activists, and two adorable grade school girls from the Washington area, wearing “Buddy Bison” T-shirts. I was not the only one to note the irony of celebrating the outdoors in an indoor venue (what, then, do you do with your cowboy hat?), but that point soon gave way to the just-released AGO Report which articulated for the first time the President’s strategy for a 21st century conservation and recreation agenda. (Disclosure: I recently served in the Obama Administration's EPA and contributed to the report.)

Open the executive summary to Chapter 1 and you learn that the most pressing challenge in the nation’s great outdoors is . . . Jobs! We need them! And fast! So the first recommendations center on streamlining federal career opportunities in nature conservancy and developing a Conservation Service Corps for young people interested in public lands and water restoration. Both fine ideas, particularly the second, which the President said would “encourage young people to put down the remote or the video games and get outside.” But the real meat comes in a later chapter on conservation and restoration.

Full textA new report from the National Research Council on Friday slams a long-delayed Army Corps of Engineers hurricane protection study, saying it fails to recommend a unified, comprehensive long-term plan for protecting New Orleans and the Louisiana coast.

You know the story: as Hurricane Katrina swept across New Orleans, the city’s levee system broke apart and billions of gallons of water poured into the city. Two independent forensic engineering reports (here and here) found the levee failures were caused by a series of design and construction flaws, stretching back over decades, which were overseen, in all details, by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The Corps has never refuted that basic point.

Congress ordered the Corps to develop plans for a more aggressive flood-control system for the Louisiana coast, insisting the Corps present “a final technical report for Category 5 protection.” (The surge associated with a Category 5 storm has about a 0.2% chance of occurring in any given year. A Katrina-level surge has about a 0.25% chance of occurring in any given year.)

According to the NRC:

Despite being given authority from the U.S. Congress for this project over three years ago, the [Army Corps’s] draft final technical report does not offer a comprehensive long-term plan for structural, nonstructural, and restoration measures across coastal Louisiana, nor does it suggest any initial, high-priority steps that might be implemented in the short term. Instead, a variety of different types of structural and nonstructural options are presented, with no priorities for implementation.

You can read more about these criticisms in Mark Schleifstein’s excellent piece in the New Orleans Times-Picayune.

Here, I want to focus on a legal point that is a lynchpin in the whole dispute. The problem with the Army Corps of Engineers' report is that it lays out a buffet of 27 alternative planning unit-level plans, but gives no indication of which ones should be pursued or what should be done next. As a result, the whole process could slip into a self-induced coma.

Full textCenter for Progressive Reform Member Scholar Robert R.M. Verchick blogs on the launch of the new project to close the Mississippi River-Gulf Outlet. Full text

Center for Progressive Reform Member Scholar Robert R.M. Verchick blogs on a proposed Executive Order on environmental justice, one of seven Executive Orders included in the Center for Progressive Reform's Protecting Public Health and the Environment by the Stroke of a Presidential Pen: Seven Executive Orders for the President's First 100 Days, issued November 11, 2008. Full text