Pennsylvania, the source of nearly half of the nitrogen that makes its way into the Chesapeake Bay, is falling dangerously behind in controlling the pollutant. Delaware is dragging its feet on issuing pollution-control permits to industrial animal farms and wastewater treatment plants. Maryland has fallen behind on reissuing expired stormwater permits and is not on track to meet that sector’s pollution-reduction goals.

These are some of the findings of a series of reports the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) issued late last week. EPA assessed the progress the seven jurisdictions within the Bay watershed—Delaware, Maryland, New York, Pennsylvania, Virginia, West Virginia, and Washington, D.C.—were making toward meeting the Chesapeake Bay Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL), a sort of “pollution diet” that is at the heart of the federally led plan to restore the Chesapeake Bay by 2025.

Along with the reports, EPA announced that it would create consequences for states that are falling behind. It will immediately increase its oversight of Pennsylvania’s agriculture sector and has proposed increasing oversight of specific sectors in Delaware, Maryland, and Virginia unless the states meet certain conditions. EPA also threatened to withhold grant money in Delaware, Maryland, Pennsylvania, and Virginia unless deadlines are met.

CPR’s newest Issue Alert, co-authored by Rena Steinzor and me, breaks down each jurisdiction’s progress and challenges in meeting the TMDL’s deadlines. In the Alert, we applaud EPA for demonstrating its willingness to take action against lagging jurisdictions.

Full text

Air pollution is a complex problem. For one, it does not adhere to state boundaries; a smokestack in one state can contribute to pollution problems in another, even a downwind state hundreds of miles away. What’s more, air pollution’s impacts are not confined to just the air. What goes up must come down, and air pollutants are eventually deposited on the ground where they are washed into rivers, lakes, and streams.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has tried for decades to address the thorny problem of interstate air pollution. Last week, the U.S. Supreme Court revived the EPA’s Cross-State Air Pollution Rule, the agency’s most recent and comprehensive attempt to tackle the issue. The decision in EPA v. EME Homer City Generation, L.P. will mean that large sources of nitrogen oxide and sulfur dioxide emissions in certain states will be subject to more stringent air pollution requirements moving forward.

Full textMaryland faces an important deadline in its long-running effort to clean up the Chesapeake Bay. By 2017, the state will be legally required to have put in place a number of specific measures to reduce the massive quantities of pollution that now flow into the Bay from a range of pollution sources in the state. Unfortunately, if the terms of a draft Chesapeake Bay Watershed Agreement are any indication, we’re going to miss the deadline.

Today, CPR President Rena Steinzor and I submitted comments to the Chesapeake Executive Council, a collaborative partnership of Bay state governors currently chaired by Gov. Martin O’Malley, arguing that the Agreement falls well short. As the first interstate agreement since EPA issued the Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) for the Chesapeake Bay, the Agreement is an opportunity to build off the TMDL and tackle the issues that plan does not address. Instead, the draft Agreement ignores some of the most pressing issues facing the Chesapeake Bay today.

Our comments urge the Bay state governors to:

This tepid don’t-rock-the-boat agreement harks back to yesteryear, when Bay states spent two full decades getting very little done. We urge Governor O’Malley, the head of the Chesapeake Executive Council, and other Bay state governors to revise the Agreement so the final document reflects the true value Bay restoration represents to the region.

Full textEPA’s budget is in free-fall. Members of Congress brag that they have slashed it 20 percent since 2010. President Obama’s proposed budget for 2015, released on Tuesday, continues the downward trend. The budget proposal would provide $7.9 billion for EPA, about $300 million, or 3.7 percent, less than the $8.2 billion enacted in fiscal year 2014.

To cope with these cuts, the agency plans to fundamentally change the way it enforces environmental laws. A draft five-year plan released in November signals that the agency is retreating from traditional enforcement measures, such as inspections, in favor of self-monitoring by regulated industries. Specifically, the agency aims to conduct 30 percent fewer inspections and file 40 percent fewer civil cases over the next five years as compared to the last five.

Even before releasing the draft plan, the agency had already begun cutting down on enforcement. In February, the agency reported a decrease in the number of in-person inspections and investigations in 2013 compared to the previous year. According to the EPA’s own report, enforcement actions in 2013 resulted in the reduction of 1.3 billion pounds of pollution, down from a high of more than 2 billion pounds in 2012. EPA conducted 2,000 fewer inspections and evaluations and initiated about 2,400 civil cases last year, continuing a downward trend since fiscal 2009 when the agency opened about 3,700.

Full textAnchorage, Alaska is more than 4,000 miles away from the Chesapeake Bay, yet Alaska joined 20 other states on Monday in asking a federal appeals court to overturn the EPA-led plan to restore the Bay, known as a Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL).

While Alaska’s interest in the Bay-wide TMDL is murky, the history of the lawsuit is straightforward. In 2009, the Obama administration issued Executive Order 13,508, directing EPA to take a leadership role in cleaning up the Bay. The Bay-wide TMDL, often referred to as a “pollution diet,” followed in 2010. It imposed strict limits on the quantities of nitrogen, phosphorus, and sediment that could be discharged into the Bay and allocated the total permissible amount of each pollutant among the Bay states and the District of Columbia, leaving it up to the states to determine how to meet the specific allocations. In 2011, the American Farm Bureau Federation and Pennsylvania Farm Bureau sued EPA claiming that the agency did not have the authority under the Clean Water Act (CWA) to issue the TMDL. In a decision this past September, U.S. District Court Judge Sylvia Rambo disagreed. The Farm Bureau immediately signaled its intent to appeal to the Third Circuit and filed its brief with the court last week. The states filed their amicus brief Monday in support of the Farm Bureau.

Full textEvery day, we are presented with more evidence of the need to inspect for environmental violations and enforce the nation’s laws. The evidence is stark in the Chesapeake Bay region where, in 2012 alone, just 17 large point sources reported illegal discharges of nitrogen totaling nearly 700,000 pounds. These violations put the watershed states behind in their efforts to restore the estuary and meet the 2025 goals of the Bay pollution diet.

The problem cries out for stronger enforcement of environmental laws, and yet EPA recently released a draft FY 2014–2018 Strategic Plan that signals that the agency will retreat significantly from traditional enforcement in the coming years. Specifically, EPA aims to conduct 30 percent fewer inspections and file 40 percent fewer civil cases over the next five years as compared to the last five.

CPR’s newest Issue Alert, which I co-authored with CPR President Rena Steinzor and Member Scholar Rob Gicksman, argues that traditional enforcement should be the last function the agency should cut because it is the most cost-effective weapon to prevent backsliding on the progress the nation has made in reducing traditional pollution.

Instead of traditional enforcement, the agency’s plan embraces a new enforcement paradigm called “Next Generation Compliance.” NextGen relies on self-monitoring and reporting by polluters, aims to make regulations “easier” for them to comply with, and replaces the way EPA measures the effectiveness of its enforcement activities with untested methods.

The Issue Alert finds that EPA’s new enforcement scheme has at least four specific shortcomings:

It relies on industry to police itself, an untested and unproven approach that on its face invites noncompliance;

It signals a clear rollback in traditional deterrence-based enforcement, a tested and proven approach;

It seeks to mask the plain harm to public health and environmental protection of congressional budget cuts with breezy, even risible assertions of improved enforcement; and

Its retreat from enforcement and related budget cuts could irreparably delay the restoration of the Chesapeake Bay and other natural treasures.

This retreat from enforcement could severely undercut regulated entities’ commitment to meet their responsibilities, exposing the public to unacceptable health and environmental risks. Enforcement should be the last function to suffer from inadequate budgetary allocations.

You can read a summary of the report here.

Full textAs congressional negotiators reconcile the House- and Senate-passed Farm Bills, they are considering two provisions that would cut off access to information about federally subsidized farm programs and threaten public health and safety.

The Farm Bill will provide farmers with billions of dollars in federal subsidies, crop insurance, conservation payments, and other grants. The vast majority of the farms that qualify for these federal dollars are incorporated businesses that turn a profit by working the land. Yet, by conjuring up idealized images of a family sharing an old-fashioned farmhouse at the end of a country lane, the farm lobby managed to convince House lawmakers to pass two provisions that would prohibit federal agencies from revealing much of the basic information about the farms. The government does not take such a hands-off approach with any other recipient of federal money.

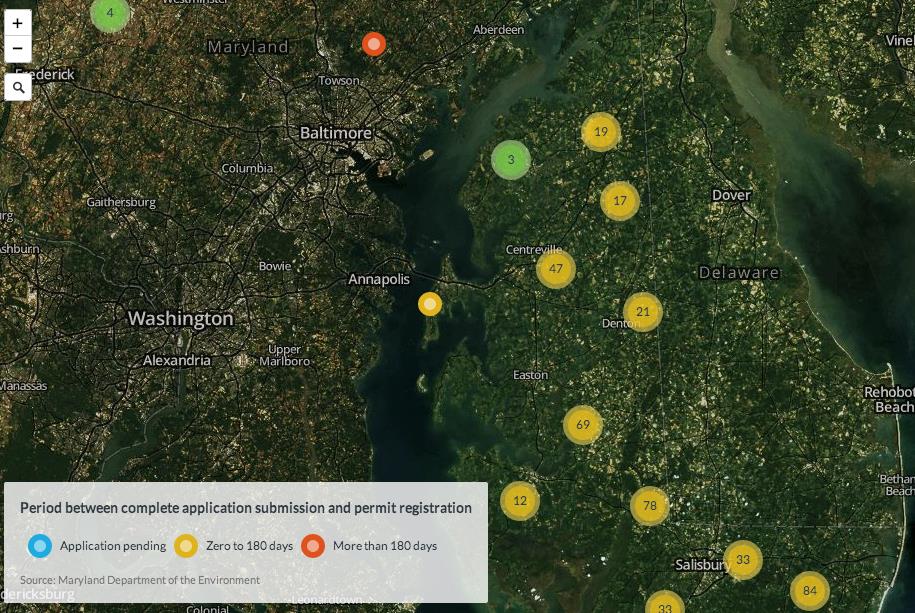

This information can be critical to maintaining public health and safety. For example, massive livestock operations, which can dump fecal bacteria, hormones, nutrients, and other waste into waterways, can threaten the health of families who live nearby. Basic information, such as the location of the farm, is often available from state agencies—CPR and the Chesapeake Commons recently developed a map of industrial animal farms in Maryland using information from the Maryland environmental agency, for example. Under the House-passed Farm Bill, useful projects like this would never be possible at a national scale.

Full textLate last month, the Center for Progressive Reform revealed that the Maryland Department of the Environment (MDE) waives pollution permit application fees for concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) in the state, and that the agency is far behind in processing such applications. Now we're able to put a number on MDE's decision: MDE is waiving $400,000 in application fees this year alone. And what might it do with that money it's choosing to leave on the table for some reason? It could speed up its delayed permitting process, for one thing.

The CAFO program was designed to be self-supporting. The idea was that the agency would collect modest fees from polluters (ranging from $120 to $1,200, depending on their size) and use that money to pay for the necessary permit writers and inspectors. By waiving the fees, MDE has shifted the responsibility of funding its program away from the polluter and instead relies on taxpayer funds. So in addition to paying a fee for their driver's licenses, car registrations, and fishing permits in the Bay, Free State taxpayers also get to pick up the tab for pollution permits for large industrial chicken operations.

This morning, CPR President Rena Steinzor and I sent Robert Summers, Secretary of MDE, a letter urging MDE to stop waiving fees. (Read the full text of the letter here).

Full textLately, press releases from the Maryland Department of Agriculture read like a broken record:

MDA Withdraws Phosphorus Management Tool Regulations; Department to Meet with Stakeholders and Resubmit Regulations

-- August 26, 2013

MDA Withdraws Phosphorus Management Tool Regulations; Department to Consider Comments and Resubmit Regulations

--November 15, 2013

The second headline is from this past Friday when MDA withdrew a proposed regulation aimed at cleaning up the Chesapeake Bay by restricting the use of manure to fertilize crops.

Manure is full of phosphorus, one of the nutrients choking the Bay. Indeed, manure runoff accounts for 26 percent of the phosphorus in the estuary. The proposed “phosphorus management tool,” developed at the University of Maryland, would have helped determine which fields were over-saturated with the nutrient. If the soil contained too much phosphorus, the farmer could not apply manure to fertilize that field.

As the agency’s press releases show, this is the second time MDA has pulled back its attempt to limit manure usage. An emergency regulation that was supposed to have gone into effect this fall was withdrawn in late August after the farm lobby complained that it could cripple the state’s poultry industry. MDA withdrew the rule this time after agricultural groups once again complained of its economic impact.

The abandonment of the manure-management tool comes at the same time that a new CPR report warns that the state’s regulation of industrial animal farms is lagging. According to CPR President Rena Steinzor, the two are closely connected.

Full textMaryland’s effort to limit pollution from massive industrial animal farms in the state is falling behind. A new CPR Issue Alert finds that the state has not registered 26 percent of Maryland’s concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) and Maryland animal feeding operations (MAFOs), missing out on tens of thousands of pounds of pollution reduction in the Chesapeake Bay.

The Chesapeake Bay is in trouble. Years of half-hearted interstate efforts to check polluting emissions and restore the nation's largest estuary have failed. The Environmental Protection Agency’s Total Maximum Daily Load (TMDL) plan for the Bay represents the Chesapeake's last, best chance of recovery. The TMDL requires all major polluting sectors—including massive industrial farms—to reduce their discharges into the Bay.

Maryland is home to at least 588 of these massive animal farms, known as concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs) and state-regulated Maryland animal feeding operations (MAFOs). To meet the TMDL, Maryland has committed to eliminating the discharge of 248,000 pounds-per-year of nitrogen and 41,000 pounds-per-year of phosphorus from all animal feeding operations in the state by 2025. Meeting this goal will require robust government oversight.

Three years into the program, however, and Maryland has fallen far behind in permitting these facilities, missing a crucial opportunity to reduce pollution to meet the TMDL. Issuing permits is the only way to  compel these facilities to follow certain best practices to limit pollutants flowing into the Bay. Specifically, the CPR Issue Alert reveals:

compel these facilities to follow certain best practices to limit pollutants flowing into the Bay. Specifically, the CPR Issue Alert reveals:

The permit writers are behind: 87 out of a total of 506 complete applications have yet to be processed, leaving operators with no clear requirements to reduce pollution and MDE with no enforceable conditions.

The CAFO program is understaffed, relying on three permit writers and the same number of inspectors. A loss of even one employee can cut the program’s productivity in half, as occurred in 2012.

Many of the applications MDE receives are incomplete: 65 of 540 CAFOs lack the required comprehensive nutrient management plans (CNMPs) that dictate how the facility is to operate to protect water quality.

MDE has so far given the industry a free ride: It has yet to collect application and annual fees for CAFO permits, which are $120 for small CAFOs, $600 for medium CAFOs, and $1,200 for large CAFOs. Collecting these fees would ensure that the program has sufficient resources to hire additional permit writers and inspectors.